At 19, Joe Tsogbe underwent his first hip replacement. In his 20s, he averaged about nine hospitalizations per year, a number that increased to more than a dozen by his 30s.

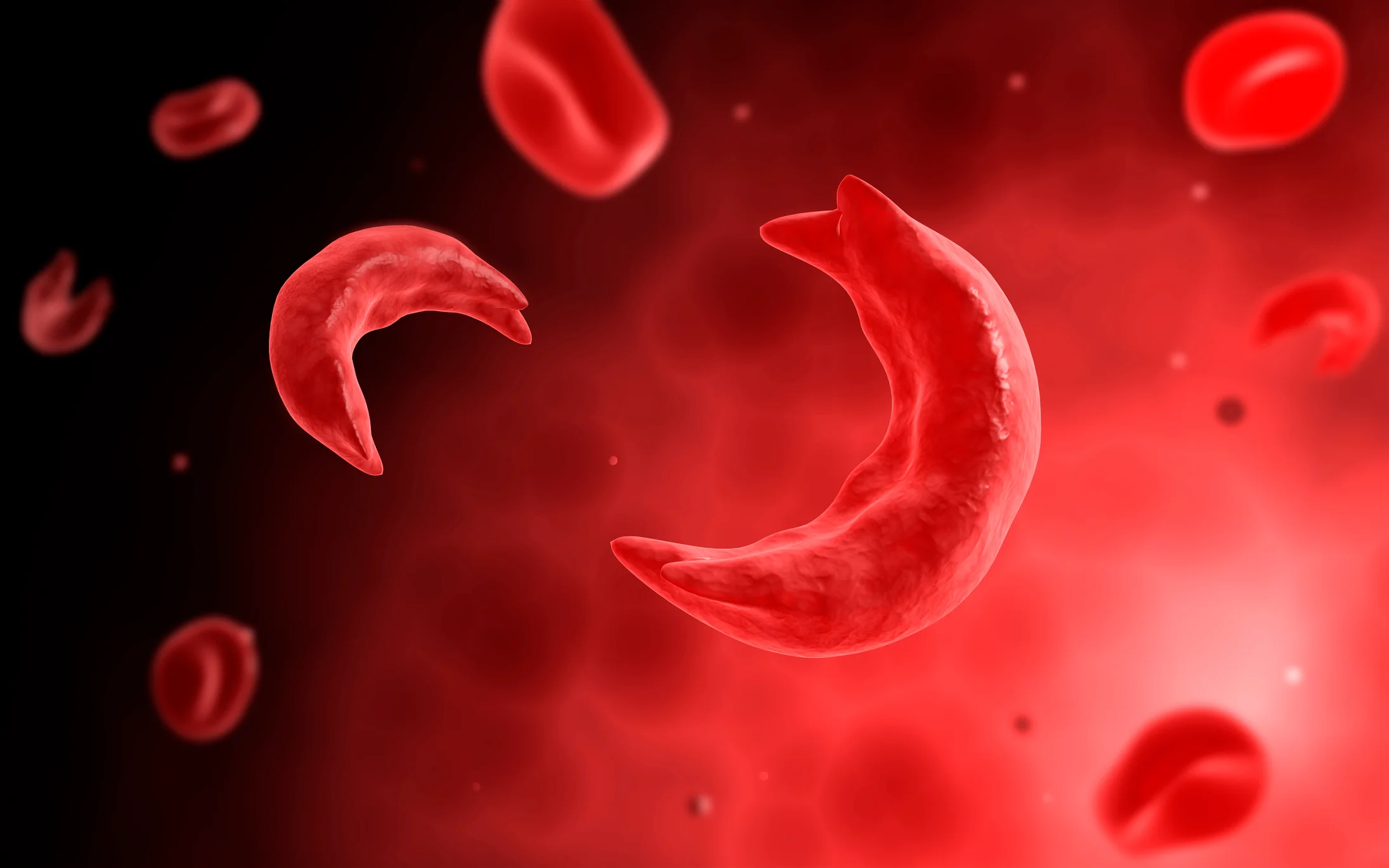

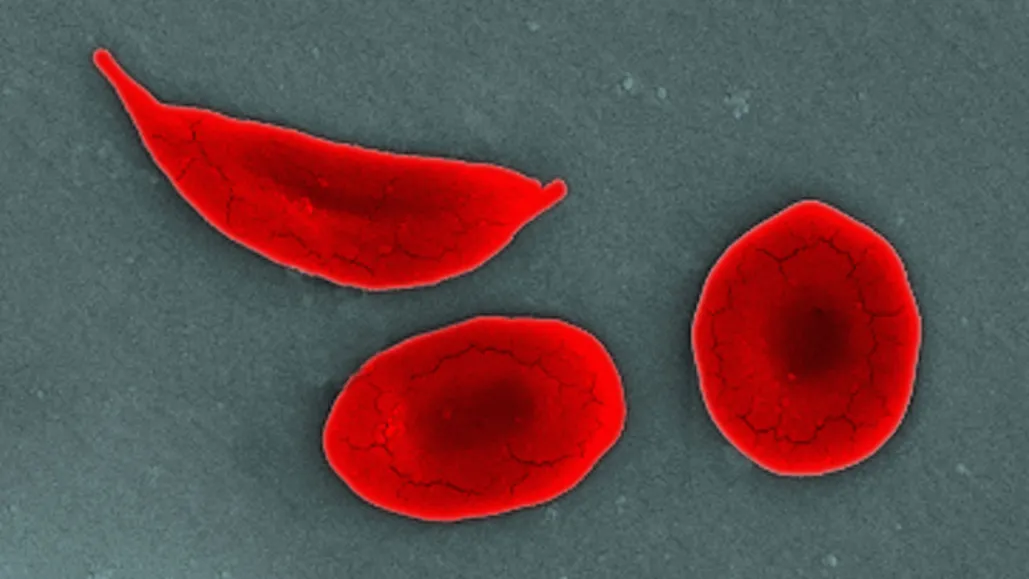

These frequent hospital visits were all due to sickle cell disease, an inherited blood disorder caused by a genetic mutation that changes normally round red blood cells into crescent shapes.

These sickle-shaped cells can become lodged in blood vessels, impeding blood flow and causing severe pain. Sickle cell disease affects approximately 100,000 people in the U.S., many of whom are Black.

Treatment options are limited, with the only cure being a bone marrow transplant, which involves receiving healthy blood stem cells from a donor. New genetic therapies aim to provide relief and eliminate the need for donor matches.

Tsogbe, now 37, participated in a clinical trial in 2021 for one such therapy known as exa-cel, co-developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR Therapeutics.

This treatment employs CRISPR technology, which was awarded the Nobel Prize, to edit DNA and relieve the symptoms of sickle cell disease.

U.S. regulators are anticipated to approve exa-cel for sickle cell patients by the end of this week. The U.K. approved it under the name Casgevy last month.

Another gene therapy from Bluebird Bio, called lovo-cel, is also under review by U.S. regulators. Although it operates differently from exa-cel, it is administered in a similar fashion and aims to eliminate pain crises. Approval for lovo-cel is expected later this month.

If approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, exa-cel would represent a significant scientific achievement, occurring about a decade after the discovery of CRISPR technology, and would be a major advance for patients seeking better treatment options.

However, the high cost of exa-cel, estimated at around $2 million per patient, could be a major test for the U.S. healthcare system. Tens of thousands of individuals could be eligible for this treatment.

In 2012, researchers Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier published a groundbreaking paper on CRISPR-Cas9, a system for editing genes.

This discovery led to a surge in companies aiming to use this technology to treat various diseases, with sickle cell disease emerging as a prominent target.

Sickle cell disease, first described as a molecular disease by scientist Linus Pauling in 1949, is most prevalent in Africa. The sickle cell gene offers protection against malaria.

People with one copy of the gene typically do not exhibit symptoms, but those with two copies—one from each parent—can suffer severe complications.

CRISPR technology can edit a patient’s genes to reactivate fetal hemoglobin, a protein that typically shuts off shortly after birth, helping red blood cells maintain their healthy shape.

This process involves extracting blood stem cells, editing them in a lab, and then infusing them back into the patient’s bloodstream.

Dr. Markus Mapara, director of blood and marrow transplantation at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, who treated patients in the exa-cel trials, explained, “We are essentially training the cells to produce more fetal hemoglobin.”

The treatment itself is administered once, but the entire process spans several months.

It involves extracting and isolating blood stem cells, modifying them in Vertex’s lab, administering chemotherapy to make space for the new cells, and then infusing the modified cells into the patient. The patient typically spends weeks recovering in the hospital.

Vertex and CRISPR established a partnership in 2015 to develop gene-editing treatments for genetic disorders, including sickle cell disease. Vertex will lead the launch of exa-cel, pending approval.

Vertex views exa-cel as a significant financial opportunity and plans to focus on the approximately 32,000 people in the U.S. and Europe with the most severe forms of sickle cell disease.

Vertex is also seeking approval for exa-cel to treat another blood disorder, beta thalassemia, with a decision expected from the FDA in March.

Despite these prospects, Wall Street remains skeptical about exa-cel’s commercial potential. Analysts project $1.2 billion in sales for exa-cel by 2028, a fraction of the $14 billion in revenue they forecast for Vertex that year, according to FactSet.

Dr. Mapara noted that it is premature to label exa-cel as a cure. However, clinical trial charts show that many patients experienced a reduction in pain crises, with some experiencing none after treatment.

“It’s astonishing,” said Mapara, who consults for Vertex and CRISPR. “The effectiveness of this treatment is clear.”

The lengthy treatment timeline, along with the risk of chemotherapy-induced infertility, might make exa-cel a challenging option for some patients.

Additionally, its availability will be limited to specialized healthcare facilities, potentially restricting access. The expected cost of approximately $2 million per patient could also deter widespread insurance coverage.

For Tsogbe, however, the cost is worth it. As a child in Togo, West Africa, Tsogbe experienced painful swelling in his joints.

After numerous doctor visits, he was diagnosed with sickle cell disease. With limited treatment options available, Tsogbe promised his mother that he would find a cure by moving to the U.S.

At 16, he moved to the U.S., where he eventually enrolled in the exa-cel trial. Since receiving the treatment about two years ago, he has not experienced a pain crisis.

Although it has not completely eliminated his symptoms or the damage caused by the disease, it has kept him out of the hospital.

Tsogbe is now more active than ever, running two entertainment companies and teaching dance—activities he loves but that previously left him exhausted.

Last year, he visited Togo for the first time since leaving in 2003, feeling like a “totally different person.” “In a way I kept my promise,” Tsogbe said.

Leave a Reply