As Cyndi Lauper famously said, “Money changes everything,” and she’s absolutely right. The pursuit of wealth, or the things that can be exchanged for it, is a fundamental driver of human behavior.

It was this quest that spurred Columbus to set sail across the ocean, seeking the riches he believed awaited him. Today, a similar drive surrounds lithium, which has become “more valuable than gold” in the race to build battery-powered vehicles.

China recognized the importance of lithium far earlier than most other nations. While others were slow to act, China was busy identifying global lithium deposits and either purchasing them outright or securing advantageous deals with those who didn’t fully grasp the mineral’s worth.

This strategy has allowed China to dominate the lithium-ion battery market, exerting control over nearly every aspect of the process, from mining to battery component manufacturing, to the production of finished cells.

For the past decade, many have lamented China’s success in securing this critical resource, fearing that the United States would remain dependent on China for this essential technology.

However, in an unexpected turn of events, China’s dominance has spurred others to seek alternatives. New companies have emerged, particularly in the Salton Sea area of California, aiming to extract lithium from salt brine.

Despite optimistic projections, these efforts are still years away from producing enough lithium to meet America’s needs. Meanwhile, Australia currently leads as the world’s largest lithium supplier.

On August 30, 2023, researchers Thomas Benson, Matthew Coble, and John Dilles published a groundbreaking paper in Science Advances announcing what may be the world’s largest known lithium deposit.

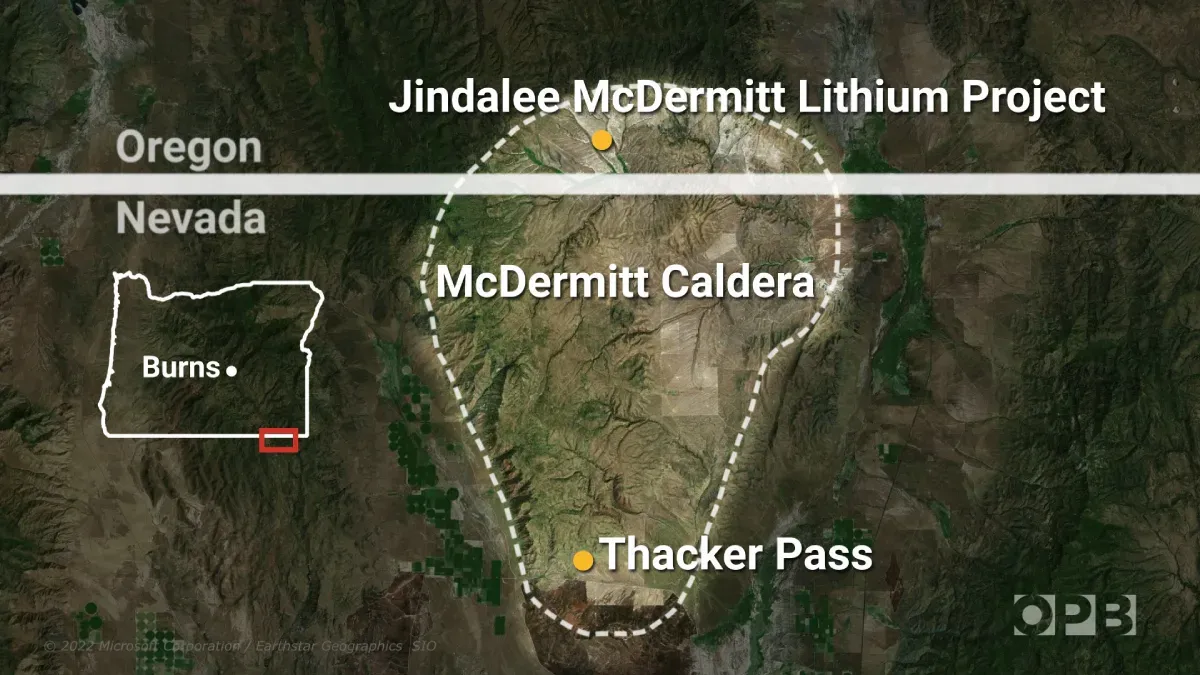

Located within the caldera of an extinct volcano in Nevada near the Oregon border, this discovery could significantly impact America’s ability to manufacture batteries independently of Chinese sources. The abstract of their paper highlights the potential of this deposit:

“Developing a sustainable supply chain for the global proliferation of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles and grid storage necessitates the extraction of lithium resources that minimize local environmental impacts.

Volcano sedimentary lithium resources have the potential to meet this requirement, as they tend to be shallow, high-tonnage deposits with low waste: ore strip ratios.

Illite-bearing Miocene lacustrine sediments within the southern portion of McDermitt caldera (USA) at Thacker Pass contain extremely high lithium grades (up to ~1 weight % of Li), more than double the whole-rock concentration of lithium in smectite-rich claystones in the caldera and other known claystone lithium resources globally (<0.4 weight % of Li). Illite concentrations measured in situ range from ~1.3 to 2.4 weight % of Li within fluorine-rich illitic claystones.

The unique lithium enrichment of illite at Thacker Pass resulted from secondary lithium- and fluorine-bearing hydrothermal alteration of primary neoformed smectite-bearing sediments, a phenomenon not previously identified.”

The researchers estimate that 20 to 40 million tons of lithium metal lie within this volcanic crater, surpassing the previously considered largest deposit beneath a Bolivian salt flat.

An analysis of the volcanic crater revealed that an unusual claystone, composed of the mineral illite, contains between 1.3% to 2.4% lithium, nearly double the amount found in more common magnesium smectite.

“If you believe their back-of-the-envelope estimation, this is a very, very significant deposit of lithium,” remarked Anouk Borst, a geologist at Belgium’s KU Leuven University. “It could change the dynamics of lithium globally, in terms of price, security of supply, and geopolitics.”

The formation of this deposit is a fascinating tale for geologists. The McDermitt Caldera was created 16.4 million years ago when approximately 1,000 cubic kilometers of magma erupted, leaving a crater filled with lithium-rich volcanic material.

Over time, a lake formed in the crater, depositing layers of lithium-rich clay. Later, volcanic activity caused hot, lithium- and potassium-rich brine to alter the clay, leading to the formation of lithium-enriched illite.

Christopher Henry, an emeritus professor of geology at the University of Nevada in Reno, described the lithium-rich material as resembling “a bit like brown potter’s clay.”

He noted the significant interest in finding additional deposits, particularly as the United States currently has only one small lithium-producing operation in Nevada.

Benson, one of the researchers, said his company expects to begin mining the deposit in 2026. The process will involve removing clay with water, separating lithium-bearing grains using a centrifuge, and then extracting lithium from the clay using sulfuric acid.

“If they can extract the lithium in a very low-energy-intensive way or in a process that does not consume much acid, then this can be economically very significant,” Borst added. “The US would have its own supply of lithium, and industries would be less concerned about supply shortages.”

The concern that America lacks sufficient lithium to meet future demand is likely exaggerated. Historically, fears of resource scarcity have often led to the discovery of new resources or the development of new extraction technologies.

The history of coal, oil, and gas industries is filled with examples of this pattern. Fracking, for instance, extended the profitability of extractive enterprises far beyond initial expectations.

As America’s need for lithium grows, the forces of the free market will likely find a way to meet that demand. Looking even further into the future, it’s possible that lithium could eventually be replaced by other, more abundant materials.

Perhaps someday, future writers will discuss “peak lithium” in the same way they once discussed “peak oil.”

In the meantime, there’s no need for alarm. Everything is progressing as it should, right on schedule.

Of course, it would be ideal if nations could learn to cooperate for the sake of preserving the Earth for future generations—but unfortunately, there’s little profit in that.

Leave a Reply